Vigilance, continuous learning are industry’s best defenses against cybercriminals.

It has become a painfully common headline: “Cyberthieves breach company’s system, steal credit card numbers, Social Security numbers, birthdates, passport numbers . . .” High-profile corporations such as Target, Equifax and Marriott all have been robbed of massive amounts of valuable consumer data in recent years, proving that even major companies with huge budgets and IT departments are not safe.

Cybercrime is not your grandfather’s smash and grab. It is a strategic, sophisticated, coordinated operation in which criminals slip in through a virtual window that a company forgot to close or through a back door that may have been closed but not locked. Hackers even disguise themselves as friendly faces and come in through main online entrances, using keys that unwitting employees freely hand over.

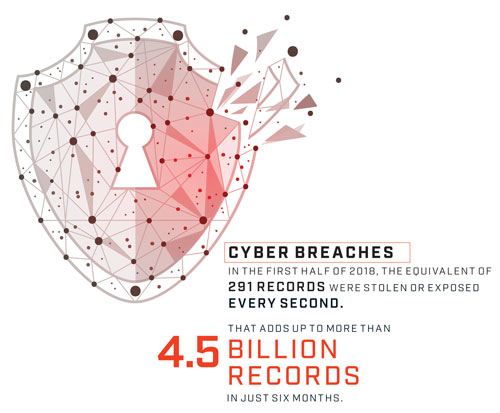

Record Number of Breaches

As we live more of our lives online, cyberspace has become a web burglar’s dream. In the first half of 2018, the equivalent of 291 records were stolen or exposed every second, reports Computer Business Review. That adds up to more than 4.5 billion records in just six months. The financial losses from these breaches can reach hundreds of billions of dollars in a very short time.

The direct selling industry, which collects billions of items of personal data from customers all over the world, is a prime target for cybercriminals, making cybersecurity a top priority right now, say direct selling executives and advocates. “Direct selling companies are among the most vulnerable to cyberattacks because of the volume and type of data they collect,” says Walter Noot, chief information officer at Salt Lake City, Utah-based USANA. Beyond personally identifiable information (PII)—such as addresses and phone numbers— and payment card industry (PCI) data, they gather other sensitive content such as Social Security and government ID numbers.

“Cybersecurity is a paramount concern for us as an industry,” says Adolfo Franco, chief operating officer at the Direct Selling Association (DSA). Feeling increasing pressure from regulators to close IT gaps or risk penalties and massive loss of data and consumer trust, many direct selling leaders are doubling down on efforts to stop intruders as far from the doors and windows as possible.

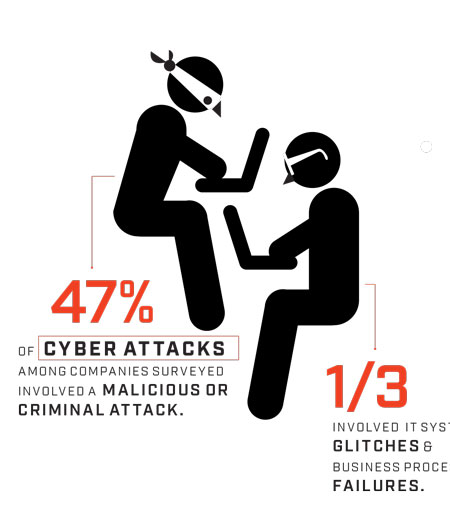

The Human Element

In a 2017 study conducted for IBM, 47 percent of cyberattacks among companies surveyed involved a malicious or criminal attack, and about one-third involved IT system glitches and business process failures. But 25 percent were due to negligent employees or contractors. That’s one in four that potentially could be prevented through proper training and increased awareness.

That kind of diligence recently saved Frisco, Texas-based PURE from handing over money to a cyberthief. Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Daren Hogge says he was about to board a plane when he got a call from his assistant. She wanted to confirm that he’d sent her an email telling her to purchase and send the codes from some Apple iTunes gift cards “immediately—so that we can use them as rewards for our Independent Business Owners (IBOs).” He had not sent that email, and while she almost bought the cards, she paused and thought, “I’d better check this out first.”

Common-sense cybersafety like this is a recurring topic at PURE headquarters staff meetings and a regular message to the company’s 60,000 U.S. and Asia IBOs. “We have found that you can’t tell someone just one time,” Hogge says. “It has to be a constant effort. The more you hear it the more it becomes ingrained in what you do.”

Stopping thieves in their tracks is everyone’s job, experts say—because the financial consequences of successful extortion or theft can cost a company dearly. Among the companies surveyed for the IBM study, the average cost of a typical breach in 2017 was $3.6 million. So-called “mega breaches” can cost a single company as much as $350 million. “There are many hidden expenses,” the study says, “such as reputational damage, customer turnover, and operational costs.”

“Direct selling companies are among the most vulnerable to cyberattacks because of the volume and type of data they collect.”

— Walter Noot, Chief Information Officer, USANA

Beyond the harm to customers and company finances, senior executives’ jobs can be at risk in the wake of attacks, too. Equifax’s chairman and CEO stepped down after his credit agency’s breach was revealed in 2017, taking the heat for the theft of PII that affected 145.5 million people. An article in TechRepublic reported recently that Paul Proctor, vice president of research and advisory company Gartner, believes the Equifax chief’s exit “will be a trend likely to continue as more breaches emerge.”

Rules and Regulations

As online privacy rules tighten—especially in Europe, under the General Data Protection Regulation that went into effect last May—direct selling companies need to stay on top and even ahead of best practices in data protection. In 2016 the DSA formed a council of chief information officers from about 15 member companies for this purpose. Considering themselves a learning group, the CIOs meet regularly to compare notes on how their companies are handling data, implementing security measures, responding to potential threats and recruiting and retaining top IT talent.

“Stopping thieves in their tracks is everyone’s job, experts say—because the financial consequences of successful extortion or theft can cost a company dearly. Among the companies surveyed for the IBM study, the average cost of a typical breach in 2017 was $3.6 million. ”

Eventually, this group may help DSA issue a set of U.S. cybersecurity guidelines for the industry, Franco says. The European DSA has already published guidelines for direct sellers in Europe, he adds. Meantime, the CIO council is gathering and processing information about the nature of current threats as well as how various levels of government are developing and enforcing regulations.

The Federal Trade Commission is scheduled to have a hearing this month on data privacy, and the DSA will be there to provide its perspective on the best ways to shield companies and consumers from cyberattacks. As always, Franco says, the association supports all regulations that are in the best interests of its members and their stakeholders and just wants to make sure “we are not burdened with unreasonable or unnecessary” rules.

California has already passed its own Consumer Privacy Act, set to take effect in 2020. But Noot says he hopes U.S. lawmakers and regulators will adopt national standards so that companies don’t have to keep track of and comply with lots of different state-level regulations.

Constant Vigilance

Executives we talked to for this story say it’s critical to have a healthy “respect” for hackers’ abilities, or rather an acknowledgment of their skills. To say that a company is immune to cybercrime is folly, according to Noot, who says “If anyone says ‘We’re totally secure,’ they should be fired. There’s no such thing.” Because believing you’re secure implies that the methods of breaking in are static, and they’re not. Hacking is an evolving science. Hogge agrees. “I don’t want to give the impression that PURE is smarter than these hackers, because these folks are genius people. They’ll take it as a personal challenge.”

So the best cyberdefense strategies are those that evolve, too. “Companies think the IT department can throw some firewalls at the system and they’re okay,” Noot says. “And that’s not enough.” At USANA, a newly appointed vice president who’s in charge of just cybersecurity has been immersed in training, he adds. The company also regularly assesses its hardware, software and IT policies—sometimes using third-party evaluators—to look for weaknesses.

“If you’re doing your best to protect everything you’ve got, if you’re equal to or better in cybersecurity than companies your size, you’re in a decent place,” Noot says.

“Cybersecurity is a paramount concern for us as an industry.”

— Adolfo Franco, Chief Operating Officer, Direct Selling Association

Doing your best includes, at a basic level, following accepted cybersafety practices like frequent password resets and reminding people not to share personal data, like login information. System monitoring is key, too. Make sure there’s always someone watching network traffic, looking for unusual activity. If, despite those best efforts, you discover you’ve been breached, be quick to announce it. Transparency will go a long way toward restoring trust with your customers, experts say.

Hogge also points out how important it is to partner with vendors, like data warehousers and accounting service providers, who have a track record of protecting consumer and IBO data. “We partner with companies that have the ability to help us thwart cyberattacks,” he says.

The bottom line is, there’s no way to completely insulate a company from intruders. It’s the stark reality of the increasingly virtual world we live in, Hogge says. “We, like everybody, wish it wasn’t, but it is. We’ve got to be diligent.”

Cyber Attacks 101

Hackers have lots of weapons in their arsenals, but companies can better defend their data and systems if employees know what those weapons look like and how they’re used. Here are five of the biggest cyberguns and how to spot them.

1. Data breach

Digital theft of sensitive data such as customer names, addresses, birthdates, Social Security numbers, company financial information.

Signs of a breach: Reports of identity theft; sensitive company data discovered freely available online; unauthorized downloads from the network; bogus email attachment opened by an employee.

2. Phishing (also known as social engineering)

A request, often for identifying or financial information, that appears to be from an organization or a person the recipient knows.

Signs of phishing: Unexpected email requests–that appear to be (but are not) from someone an employee knows—for money or sensitive data; hyperlinks that don’t match what the text of the email says they should be; poor grammar and spelling in emails; “URGENT” in subject lines.

3. Malware

Software intended to damage or disable computers and computer systems; can come from web downloads such as attached files or from clicking on internet ads.

Signs of malware: Strange ads or windows popping up even when a user isn’t logged into a web browser; ads with inappropriate content that might be difficult to close; ads that display flashing colors while blocking what the user is trying to view.

4. Ransomware

Programs that cyberblackmailers use to lock up systems and then charge a fee to release them.

Signs of ransomware: Messages that a computer doesn’t have the application to open a file; odd or missing file extensions; explicit demands for money to restore access.

5. Distributed denial of service attack

Programs that cybercriminals use to flood a network with traffic, crashing the system and preventing authorized users from getting to their email, files and online accounts and other services.

Signs of DDoS attack: Unusually slow network; suddenly inaccessible websites.

Best Cyberdefense Practices

Walter Noot, chief information officer at Salt Lake City, Utah-based USANA, has been in the technology industry for nearly 25 years—many of those years closely involved with direct selling companies. And until about 10 years ago, the internet barely figured into most direct selling operations, so no one cared that much about cybersecurity. Things have changed.

Noot says USANA has spent tens of millions of dollars on cyberprotection in the last few years, its strategy built on a foundation of these four pillars:

- Internal Processes—including acceptable use policies for software, systems and devices

- Software—for monitoring network activity, defending systems and recovering lost or stolen data

- Architecture and Infrastructure—configuring networks to resist penetration and implementing the proper number and types of firewalls and disaster recovery systems

- Culture—the priority a company puts on data safety and the money it’s willing to spend on it

Noot and other experts also say it’s important to examine the kinds of data you’re collecting and to know why you’re collecting it. General Data Protection Regulation guidelines explicitly address this idea of being deliberate about gathering and keeping data. Whether or not your company does business in Europe, you would be wise to ask yourself these questions:

Is data protection top of mind for everyone at this company? Are we privacy-aware?

Who collects our data and where is it kept? How long do we keep it and why? What do we use it for?

Do we give customers clear information about what we collect from them, and can they easily opt out of emails and other forms of marketing from us?

Are we tracking data privacy news and regulatory reform efforts?